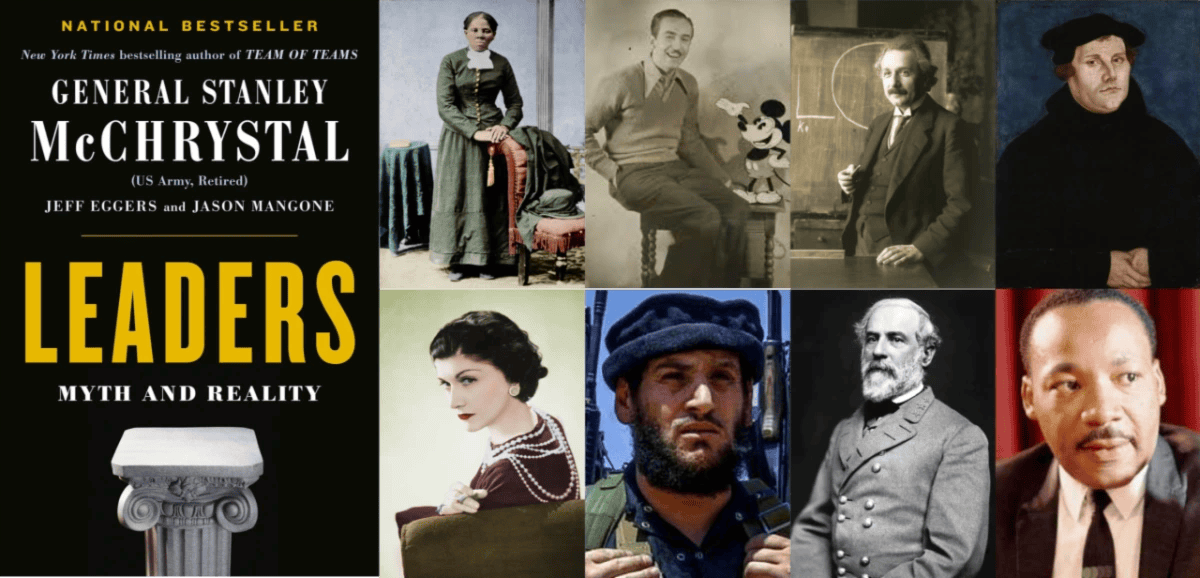

| You should read Leaders: Myth and Reality by Gen Stanley McChrystal (retired), Jeff Eggers (both of The McChrystal Group ) , and Jason Mangone . Here’s why. First is breadth and diversity of example. Common to ‘hot’ topic books (innovation, entrepreneurship, and AI for instance), is “picking on the dependent variable,” using examples that were (1) successful in (2) undertakings with which author and reader identify. About leadership, it’s not surprising that West Point has statues and course work related to victorious generals, and the Naval Academy celebrates graduates who held high command. MBA curriculums are replete with ‘titans of industry.’ At MIT , we decorate our campus with tributes to Newton, Ptolemy, and Galileo. Leaders steps out of self-affirming echo chambers with diverse examples —race, sex, context, era, and cause. Outside of Leaders you’re not likely to meet Harriet Tubman, Albert Einstein, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, and Walt Disney in the same book. Hopefully, after reading Leaders , readers will be prompted to look outside their fields for lessons. The second reason to read Leaders is depth. With Coco Chanel or fellow Frenchman Robespierre’s histories, Leaders goes beyond recitation of life facts—as if from a curriculum vitae. It puts subjects in context of societal forces and historic currents in which they existed . For the contemporary readers, Martin Luther King Jr. might seem as distant a figure as Martin Luther, so exploring these periods is mind expanding. For instance, Leaders details the times of Zheng He, a 14th century Chinese admiral. Learning how he helped establish Chinese maritime superiority, and appreciating that mythology about him shapes China’s current views of its rightful place, puts construction of islands in the South China Sea in historical and emotional context. Likewise, unpacking the milieu from which al-Zarqawi emerged frames the latest reports out of Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria. The third reason to read Leaders is the conclusions that emerge from the diversity of examples and the depth of historical treatment . This is not history as ‘great man (or woman) theory,’ that events bumble along until titanic personalities singularly redirect them. The subjects in Leaders had influence, but it was conditional. Impact depended not only on actions of the subjects, it also depended on the context in which those were taken, and it depended the concerns and biases of those being led. That leads to a more complex but accurate description of what leadership is as well as to a more useful prescription of what leaders need to do . Good leadership doesn’t emerge just from internally focused self-improvement. It requires acquiring an empathetic appreciation of one’s surroundings too. I suppose everything has its rituals, so too with a book review; at some point you toss in a critique. In deference to that convention, it’s worth noting that subjects in Leaders work through networks that amplified their impact. For instance, it mattered that Max Plank was president of the Berlin Physical Society, editor of Annalen der Physik , and, more generally, the one to “curate the eco system that enabled a lowly bureaucratic [Albert Einstein] to submit a paper that would offer the world its most important advances in physics in more than two hundred years.” It raises the question—out of what do such networks emerge deliberately or organically? To that point, I’ll suggest you digest Team of Teams , a tremendous book in which Gen McChrystal and his co authors describe the reasons, means, and consequence of building a system that was far more than the mere sum of its parts. I’ll conclude with a fourth reason to read Leaders , to understand those with whom we vest tremendous responsibility . It’s been some four decades since the USA ended the draft, depending on a volunteer military instead. That ‘division of labor’ and our other social stratifications mean certain groups are well represented in the military while others have little familiarity with those in uniform. Even if you can say, “Yeah, but I know a guy or gal…” the odds are minuscule that you know a flag officer (i.e., an officer with one to four stars). There are approximately 650 flag officers in a military of 2 million (active and reserves) in country with a population nearly 330 million. You might say, “So what? I haven’t met a farmer but eat food, never met the head of Apple or Intel, but still use the product?” For those, you may not know people responsible for the products and services they provide, but you all communicate by the decisions they make about what to offer and the ones you make about what to buy, use, or consume. With the military—our relationship is not one of interactive customer-supplier . It’s one where tremendous authority to act on our behalf and tremendous responsibility to do so well is delegated to people most of us don’t know . Stan McChrystal has been building a post-retirement career that includes writing thoughtful books drawn from his decades in uniform, at the highest levels of command. He does so his voice and his thinking—often self-reflective and self-critical comes through. The military does work that’s outside most of our sights but which is tremendous in its economic costs, importance in projecting/protecting our interests, and significant in expressing our values. Leaders , as is true of Stan McChrystal’s other books, provides a window into the thinking and doing of those who act in our stead in situations few of us well understand . |

| Steven Spear DBA MS MS Principal, See to Solve LLC Senior Lecturer, MIT Sloan School of Management Senior Fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement Author, The High Velocity Edge |

| For more on leading an organization to create conditions for high speed learning and experimentation, as practiced at Toyota, check out chapter 9 in The High Velocity Edge. |

Read Other Article: Herding Cats, Unpacking Chaos, and Why Two-Pizza Teams & APIs Matter