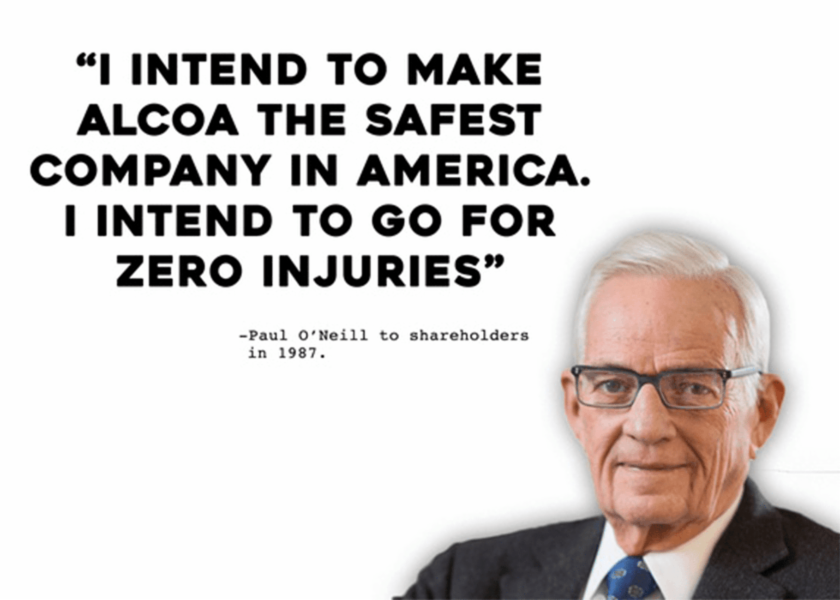

| The Honorable Paul O’Neill, former CEO of Alcoa and 72 nd Secretary of the Treasury passed away last weekend. He’ll be eulogized fairly and enthusiastically for his stewardship of Alcoa, which enjoyed huge success during his tenure, and for his public outspokenness during and about the George W. Bush administration . He’ll receive well-earned thanks for his civic leadership in Pittsburgh, both for its regional effort to markedly improve healthcare and also its ambitious waterfront redevelopment . It is no exaggeration that Paul’s corporate, governmental and civic/volunteer work improved the lives (and saved the lives) of multitudes. It’s a shame that COVID prohibitions will mean the accolades that his family deserves to hear personally will have to be received through the distancing media that’s our current normal. Into the mix of gratitude and praise, I’d like to offer thoughts, having had the privilege of working with Mr. O’Neill for more than 20 years, long enough and close enough that I’m comfortable counting him as mentor and even as a friend. Woven through the diverse roles Paul played were consistent values that were continuously re-expressed. One was that that everyone counted. Expectations of fairness, respect, and consideration weren’t tied to station in life. They were equally deserved. A second was that no matter the situation, it could be made much better were sufficient time and creativity dedicated to improving it.  Here’s a defining illustration. When Paul took over at Alcoa, the chance of getting hurt on the job was roughly 2% a year. Putting that in practical terms: if you worked on the floor, then the odds were that you suffered meaningful injury at some point in your career. If you ran a facility, then it was ordinary for you to be making “the call” to family members explaining what had happened to their loved ones. That risk was squashed to under 0.1%. In practical terms that meant that during a decades long career at Alcoa, you likely wouldn’t get hurt, nor would you know someone who did. If you managed people, “the call” was not in your routine. That achievement was from the convergence of the two values of equality and confidence in the possibility of betterment. Paul would explain state that “we” (eg Alcoa leadership) didn’t have “the right” to ask people to come to work knowing they were likely to leave less well off than when they arrived. In fact, he would say, if someone willingly gave you a day of their lives, you owed it to them that they end the day better than they had started. After all you were better off from the day they gave you.  (click here for Chapter 4 of The High Velocity Edge , with a case about Alcoa, a slightly different spin on Alcoa’s experience in this article ” Fast Discovery .”) “Hard-nosed” managers of the era might have protested that this whole “safety thing” was nice and idealistic, but it didn’t acknowledge that businesses existed for the sake of making money, that there were inevitably tradeoffs among safety, quality, cost, and the like. Therefore, the “hard-nosed” would say, people had to just accept risks that went along with making products from molten metal, with forging presses, and the like. The same dismissive logic justified industrial pollution and product failures. “There’s a cost to better, you know.” To put this in some context, the cultural icons of business in those days included Tom Wolfe’s 1987 Bonfire of the Vanities and 1989’s Barbarians at the Gate by Burrough and Helyar. During Paul’s tenure as Alcoa CEO, “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap was popularized for his butchery work at Sunbeam, and Jack Welch was the much accoladed, enormously compensated head of GE, who ran a management system that was, in all effect, corporate Survivor. Paul waved away their zero-sum, trade-off minded, win-lose beliefs as nonsense. The reason there were risks to wellbeing wasn’t because aluminum and its associated processes were inherently hostile—imagine a cartoon aluminum ingot conspiring with its fellow ingots at night about what mischief they would cause the next day. Rather, aluminum and its processes weren’t understood well enough for people to have perfect experiences. However, with a sufficiently energetic approach of calling out problems early and often (these were obvious indications of things not yet mastered) and having those problems trigger experimentation to build better understanding, perfection could be relentlessly pursued. And there was a subtle but critical wrinkle. This drove outstanding outcomes simultaneously across many metrics for many stakeholders. If we see what we don’t understand about safety, then it’s likely the same lack of understanding compromises everything else about which we care. This truth was proven out that seeing problems early and often everywhere would let us solve problems across the board and wildly raise performance. Not only did Alcoa achieve near perfect workplace safety, all other metrics improved to the point that Alcoa was one of the highest performing publicly traded stocks during the 1990s. It looked more like a tech startup than a decades-old heavy industry behemoth. And this made perfect sense. Alcoa had spent years converting itself from an enterprise focused largely on the physical product it generated each day to an enterprise that was using physical processes to generate deeper and better useful knowledge. A gigantic industrial that belonged as much on the NASDAQ index as on the DJIA. The new leader of a recently acquired site, one that had been available for purchase because of its underperformance and labor-management disfunction, but those values into practice. He was building a quality team. When the names of ‘exemplary’ hourly employees were compiled (ie those who hadn’t rocked the boat under previous management), he requested a different list—those of represented labor who had filed the most grievances. When that new plant manager asked those guys to be on the team, they asked, “Why us?” His answer? They’d been doing the right thing: seeing what was wrong and calling it out. The real problem was no one had been listening. Because that local manufacturing leader operationalized those two values in that way and others—everyone counts and things can be much better—that plant went from being awful to one of the best in the country in about a year. After retiring, Paul could have slipped in the celebrity executive role, appearing on panels, participating in commissions, and giving highly remunerated reminiscent conference talks about his time as an industrial titan. Instead, Paul took lessons learned from Alcoa and focused them hot and heavy on medical care. Why, he challenged, were staff in area hospitals more at risk of getting hurt on the job than people working with metal that melted at 1200° F? Why were patients too often leaving acute care in worse shape than they arrived because of process breakdowns like mismedication, wrong side surgery, and hospital acquired infections? The provocative answer he hurled was that when little things went wrong, they were complacently worked around rather than triggering an Alcoa like dynamic of swarming them and solving them. Out of the conviction that things could be better for all patients and all staff grew Pittsburgh’s regional healthcare initiative and it’s ‘perfecting patient care system.’ Area hospitals reduced complications 70, 80 and 90% with some driving them to zero—surgical site infections at the Pittsburgh VA, central line infections at Alleghany General, with UPMC achieving all sorts of betterment in terms of quality, cost, and access to care. As one parting example, Paul brought the same convictions that everyone mattered and that everything could be immeasurably better to government. One might picture Treasury Secretaries as being absorbed by the market fluctuations and concerned about the public and political response to regulatory pronouncements. Those were certainly among Paul’s concerns. Paul thought beyond that. On joining the Cabinet, he walked President Bush through a passage connecting the Treasury building to the White House to show off all sorts of discarded equipment and furniture. Why? What does this say about our commitment to quality if this is how we maintain the public property in which we work; what does it say about our commitment to safety if this is how emergency accesses are littered? When he started asking what the Department produced each day—the answer included reports and analyses. Paul asked then what is the value of information if it takes the government months to close its books each time? Adopting a similar approach used at Alcoa, of calling out obstacles as they were experienced, the time was reduced to just a few days. Not only that, all the creativity required to work through the previous, unworkable process could be liberated for bona fide value creating purposes.  As a final example, Paul’s beliefs that things can be much better and they should be for everyone, I think, motivated his Oscar and Felix 10-day trip to Africa with U2’s Bono. The Honorable Paul O’Neill’s value-driven life has ended. So many are better for it. A meaningful tribute would be to honor those values by their continued practice. Steve Spear is a Senior Lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, Principal of HVE LLC, and author of The High Velocity Edge . His work with Paul O’Neill included helping develop and deploy the Alcoa Business Syste (click for book by Keith Turnbull, key leader on ABS’s creation) and initiating the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative’s perfecting patient care system . Their relationship continued during Mr. O’Neill’s period as Treasury Secretary and afterwards when they would periodically share speaking engagements. Click on video below to hear Paul O’Neill explain his values and approaches… |

Steven Spear DBA MS MS Principal, See to Solve LLC Senior Lecturer, MIT Sloan School of Management Senior Fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement Author, The High Velocity Edge |

| Click here for sample chapters from The High Velocity Edge • leadership and crisis recovery (chapters 9 and 10) • accelerating development of break through technologies (chapter 5) |