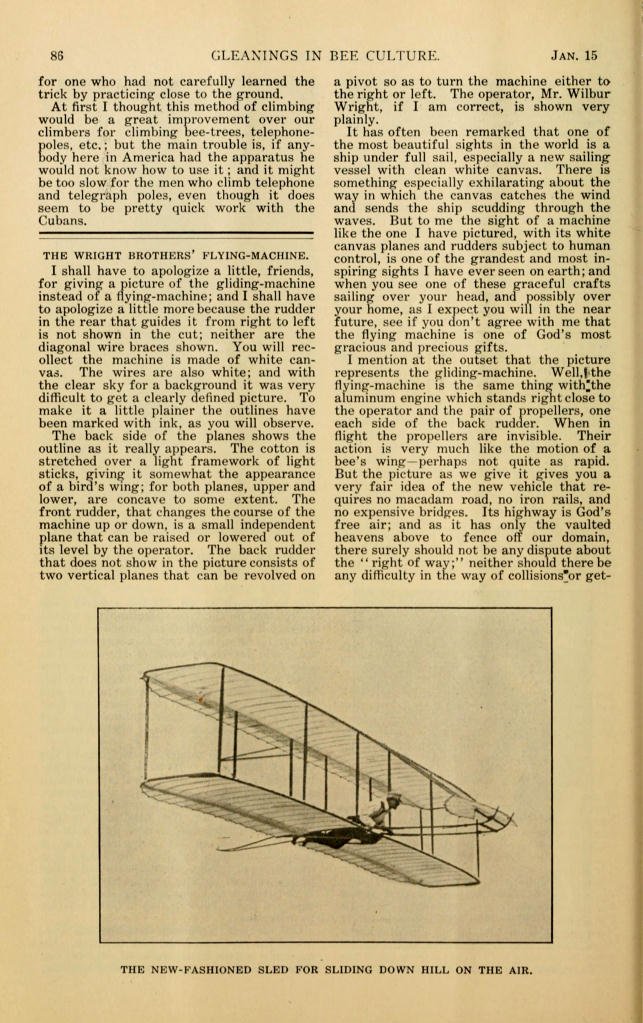

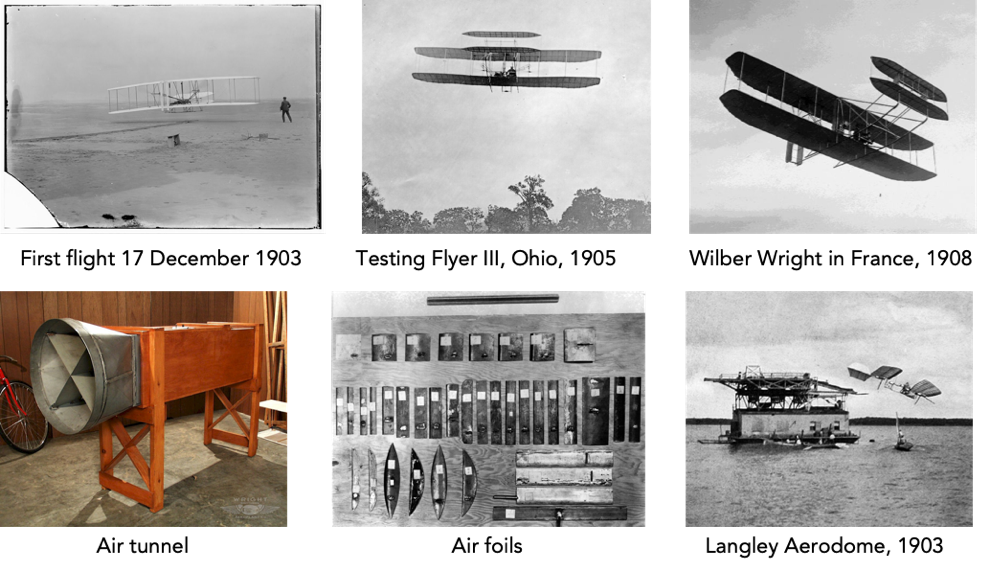

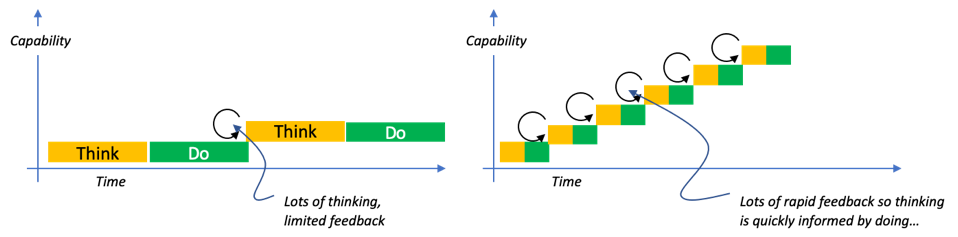

| “ The best dividends on the labor invested have invariably come from seeking more knowledge rather than more power. ” – Orville and Wilber Wright Quoted in The Wright Brothers , David McCullough, 2015.  While celebrated for achieving the first powered flight of a heavier-than-air, person carrying aircraft in 1903, that wasn’t the sole or even the greatest source of the Wright brother’s renown. After all, they didn’t receive press coverage until 1905, and that was from Amos Root, editor of Gleanings in Bee Keeping . It was in 1908 that they became celebrities, with Wilber setting world records for flight duration in France with Orville making similar demonstrations at Fort Myer in Virginia.   Yet, the whole of their success to that point had cost somewhere around $1,000. In contrast, the Smithsonian’s Samuel Langley spent $50,000 in funding, but was unsuccessful in getting his contraption to fly, and there were numerous French aeronautical dilettantes who, though well-funded, couldn’t approach the capabilities the Wright’s were demonstrating. Why is that? Because the Wright’s rivals thought long and hard in pursuit of a conceptual solution and then crystalized their thinking by building what they had in mind. Of course, what they had in mind was imperfect as were the resulting works of their hands.  The Wrights took a decidedly different approach. The seemed to operate off the assumption that they didn’t yet understand, so they had to relentlessly experiment—at high speed and low cost. Model gliders flown like kites, months spent with gliders at Kitty Hawk modifying structures and flight controls while building flying experience, a self-fabricated wind tunnel in which they could test scale models of airfoils to better understand how to generate lift, etc. Acting as if they were trying to understand a developmental technology, they gave themselves far more opportunities for feedback generating experiences to build knowhow quickly.  That should help inspire amplifying an aggressive learning dynamic around technologies that seem to think themselves still development. True, some would argue that, given schedule demands, “we don’t have time to learn.” Rather than resort to a dismissive, “But, you do have time to remain stupid,” (I tried that once; not so effective) please remind them that the Wrights got to a better answer faster, and at a fraction of the cost, because they were always looking for opportunities to discover something new. Their accomplishments were unique. Their approach conducting their work with new understanding as a deliberate output is universal. |

| Steven Spear DBA MS MS Principal, See to Solve LLC Senior Lecturer, MIT Sloan School of Management Senior Fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement Author, The High Velocity Edge |

| For the Navy’s experience building its nuclear propulsion program with an experimental discipline , please see chapter 5 (click for sample) of The High Velocity Edge (click on the cover for the book). |

| In truth, if we factor in the labor costs for the Wright’s project, it gets to be more than the $1,000 in raw materials that they reported. However, still way less than Langley’s effort. Using their sister’s daily wage as a basis, and assuming they could have way out earned her, and then accounting for the number of days they committed to the project, more or less, we still get half the cost to succeed that he spent on failure. |

|